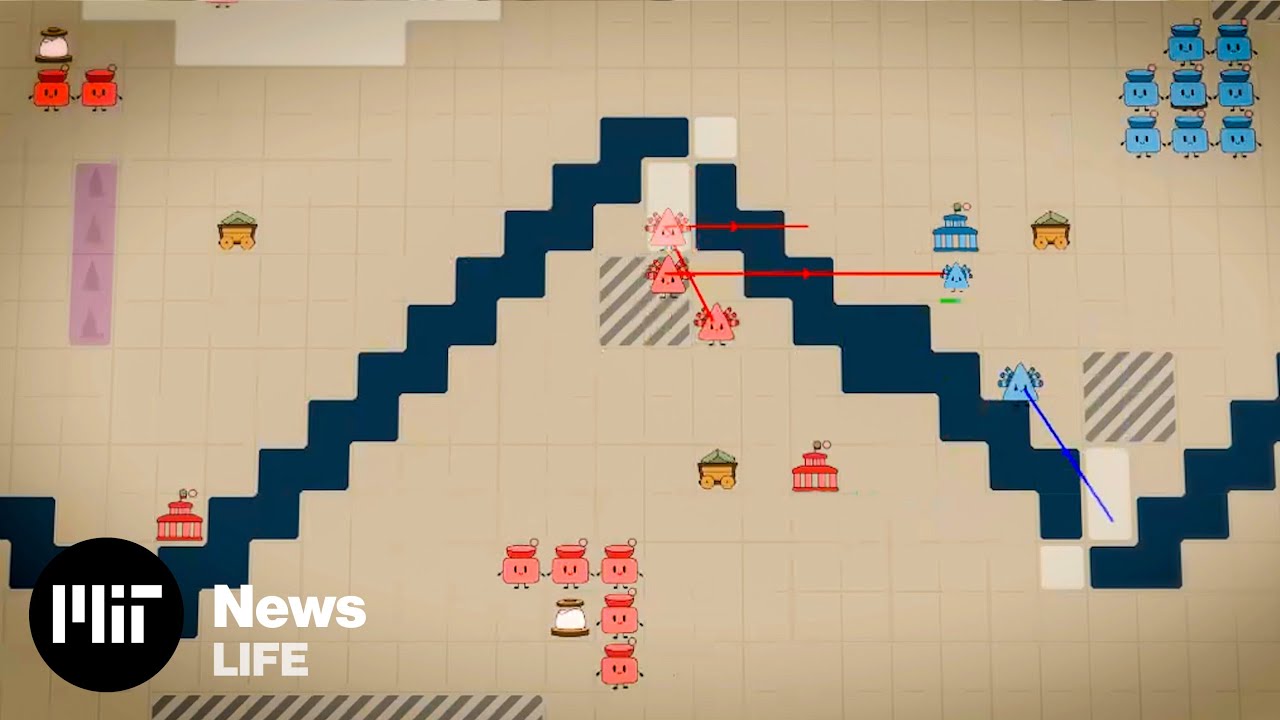

In a packed room in MIT’s Stata Center, hundreds of digital robots collide across a giant screen projected at the front of the room. A crowd of students in the audience gasps and cheers as the battle’s outcome hangs in the balance. In an upper corner of the screen, the people who have programmed the robot armies’ strategies narrate the action in real time.

This isn’t the latest e-sports event, it’s MIT’s long-running Battlecode competition. Open to student teams around the world, Battlecode tasks participants with writing the code to program entire armies — not just individual bots — before they duke it out. The resulting dramatic, often-unexpected outcomes are decided based on whose programming strategy aligns best with the parameters of the game and the circumstances of the battle.

The unique competition pushes teams to spend hours coding and refining their armies in a quest for the perfectly crafted game plan. Since 2007, the competition has involved high school and college students from around the world, upping the intellectual ante as people with diverse backgrounds tackle the open-ended challenge.

“We change it every year, so there’s new rules, new types of robots, new actions they can do against each other, and a new goal for how to win,” Battlecode co-president and MIT sophomore Serena Li said before this year’s final match on Feb. 5. “The strategies change every year because the game changes.”

MIT was especially well-represented in this year’s final tournament. Of the 16 finalist teams, three were made up entirely of MIT students, while another included three MIT students and one Yale University student. The winning team was made up of students from Carnegie Mellon University and Georgia Tech.

Although this year’s competition is officially closed, the hard work and long hours required for success in Battlecode often create a bond among participants that lasts far beyond the tight timeline of the competition.

“The spirit of the competitors is what makes the program so great,” fellow co-president and MIT junior Andy Wang says. “There’s always teams looking to create more and more advanced robots and heuristics to solve this thing, and people are putting in all this work and dedication, only to be matched by competitors doing the same thing. It creates a really incredible atmosphere every year.”

Setting the code

Since the early 2000s, Battlecode has given students a specified amount of time and computing power to write a program for armies of bots that battle in a video-game-style tournament.

When the program kicks off in January, participants are given the Battlecode software and the year’s game parameters. Throughout Independent Activities Period (IAP), which MIT students can take for course credit, participants learn to use artificial intelligence, pathfinding, distributed algorithms, and more to make the best possible strategy.

“This is a game that’s too complicated to play manually,” explains MIT senior Isaac Liao, who won the main tournament last year. “You can’t control every unit because there are hundreds of them and you’re going for 2,000 turns.”

Battlecode includes tracks for first-time MIT participants, U.S. college students (including MIT students who have competed before), international college students, and high school teams.

“The ability for anyone to compete really opens up the opportunity for everyone to try their skills on an even playing field,” Wang says. “High schoolers and international students do really well, and it’s cool because a lot of these teams will stick together and keep contacting each other even after high school.”

Following a month of refining their strategies, teams begin competing in tournament matches that lead up to the final event. Battlecode’s organizers fly in the international finalists and set them up in a hotel, where they often meet in person for the first time after weeks of online back and forth. Liao, who has competed for several years, says he still keeps in touch with former competitors.

The final battle is played out in front of a live audience at MIT, with the top teams receiving cash prizes.

Over the years, there have been many memorable events. One year an MIT student broke the game by figuring out how to leave the software space designed for contestants. (He kindly informed organizers of the flaw before the actual tournament). Another year organizers threw a new variable into the battles: zombies. A team made the finals by hiding a bot in the corner of the screen and letting the rest of the bots turn to zombies to consume the opposition.

This year’s total prize pool was over $20,000. Organizers made about 200 T-shirts to give out before the final event and quickly ran out.

The unpredictable final match makes for a tense scene as competitors are given a mic to explain the strategies unfolding on screen in real time.

Wang says organizing the event, which has increased in complexity with the inclusion of international players, is hectic but fun.

“The Battlecode members are all really friendly and welcoming, and it’s a great time running the actual event and meeting all these new people and seeing this project you work on all semester come together,” Wang says.

Indeed, the ultimate legacy of Battlecode might be the friendships formed through the intense competition.

“A lot of teams are made of students who haven’t worked together too closely,” Wang says. “They found each other through the team-building process or they know each other casually, but a lot of them end up sticking together and go on to do a lot of things together. It’s a way to form these lifetime acquaintances.”

Skills that last a lifetime

A number of current and former players noted the skills required to have success in Battlecode transfer well to startups.

“Rather than other competitions where it’s just you in front of a computer, there’s a lot to be gained from teamwork in Battlecode,” says senior and former president Jerry Mao. “That really transfers into industry and into the real world.”

This year’s sponsors included Dropbox and Regression Games, which were both founded by past participants of Battlecode. Another past sponsor, Amplitude, was founded by Spenser Skates ’10 and Curtis Liu ’10, who met during Battlecode and have been working together ever since.

“There are a lot of parallels between what you’re trying to do in Battlecode and what you end up having to do in the early stages of a startup,” Liu says. “You have limited resources, limited time, and you’re trying to accomplish a goal. What we found is trying a lot of different things, putting our ideas out there and testing them with real data, really helped us focus on the things that actually mattered. That method of iteration and continual improvement set the foundation for how we approach building products and startups.”

Beyond startups, participants and organizers said Battlecode can prepare students for a number of careers, from quantitative trading to training AI systems to conducting research. Perhaps that’s why students keep coming back.

“The most important skills for success are a lot of iteration and perseverance and willingness to adapt on the fly — basically to change how you’re working quickly,” Wang says. “You see what other teams are doing and you’re not just competing but also talking to them, studying what they’re doing well, and adding their strengths to your bots. I think those skills are important anywhere, whether you’re building a startup or doing research or working in a big company.”