The search for life beyond Earth has largely revolved around our rocky red neighbor. NASA has launched multiple rovers over the years, with a new one currently en route, to sift through Mars’ dusty surface for signs of water and other hints of habitability.

Now, in a surprising twist, scientists at MIT, Cardiff University, and elsewhere have observed what may be signs of life in the clouds of our other, even closer planetary neighbor, Venus. While they have not found direct evidence of living organisms there, if their observation is indeed associated with life, it must be some sort of “aerial” life-form in Venus’ clouds — the only habitable portion of what is otherwise a scorched and inhospitable world. Their discovery and analysis is published today in the journal Nature Astronomy.

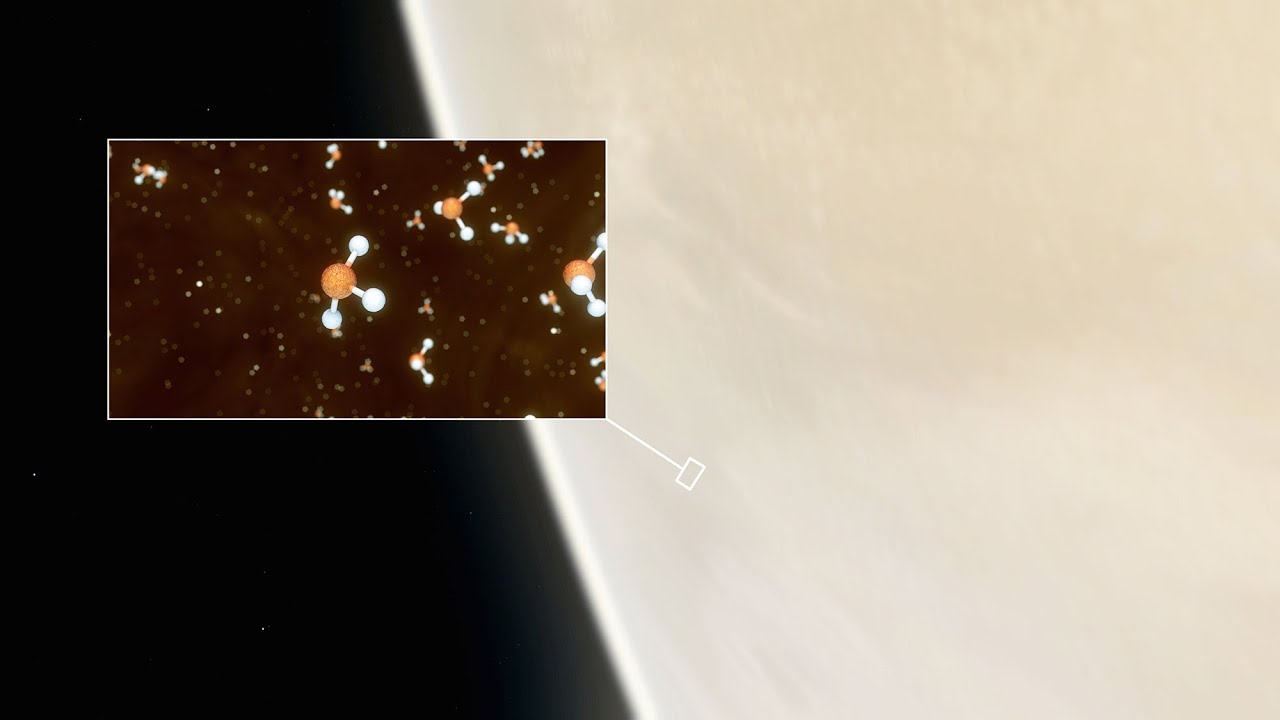

The astronomers, led by Jane Greaves of Cardiff University, detected in Venus’ atmosphere a spectral fingerprint, or light-based signature, of phosphine. MIT scientists have previously shown that if this stinky, poisonous gas were ever detected on a rocky, terrestrial planet, it could only be produced by a living organism there. The researchers made the detection using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii, and the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) observatory in Chile.

The MIT team followed up the new observation with an exhaustive analysis to see whether anything other than life could have produced phosphine in Venus’ harsh, sulfuric environment. Based on the many scenarios they considered, the team concludes that there is no explanation for the phosphine detected in Venus’ clouds, other than the presence of life.

“It’s very hard to prove a negative,” says Clara Sousa-Silva, research scientist in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS). “Now, astronomers will think of all the ways to justify phosphine without life, and I welcome that. Please do, because we are at the end of our possibilities to show abiotic processes that can make phosphine.”

“This means either this is life, or it’s some sort of physical or chemical process that we do not expect to happen on rocky planets,” adds co-author and EAPS Research Scientist Janusz Petkowski.

The other MIT co-authors include William Bains, Sukrit Ranjan, Zhuchang Zhan, and Sara Seager, who is the Class of 1941 Professor of Planetary Science in EAPS with joint appointments in the departments of Physics and of Aeronautics and Astronautics, along with collaborators at Cardiff University, the University of Manchester, Cambridge University, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Kyoto Sangyo University, Imperial College, the Royal Observatory Greenwich, the Open University, and the East Asian Observatory.

A search for exotic things

Venus is often referred to as Earth’s twin, as the neighboring planets are similar in their size, mass, and rocky composition. They also have significant atmospheres, although that is where their similarities end. Where Earth is a habitable world of temperate oceans and lakes, Venus’ surface is a boiling hot landscape, with temperatures reaching 900 degrees Fahrenheit and a stifling air that is drier than the driest places on Earth.

Much of the planet’s atmosphere is also quite inhospitable, suffused with thick clouds of sulfuric acid, and cloud droplets that are billions of times more acidic than the most acidic environment on Earth. The atmosphere also lacks nutrients that exist in abundance on a planet surface.

“Venus is a very challenging environment for life of any kind,” Seager says.

There is, however, a narrow, temperate band within Venus’ atmosphere, between 48 and 60 kilometers above the surface, where temperatures range from 30 to 200 degrees Fahrenheit. Scientists have speculated, with much controversy, that if life exists on Venus, this layer of the atmosphere, or cloud deck, is likely the only place where it would survive. And it just so happens that this cloud deck is where the team observed signals of phosphine.

“This phosphine signal is perfectly positioned where others have conjectured the area could be habitable,” Petkowski says.

The detection was first made by Greaves and her team, who used the JCMT to zero in on Venus’ atmosphere for patterns of light that could indicate the presence of unexpected molecules and possible signatures of life. When she picked up a pattern that indicated the presence of phosphine, she contacted Sousa-Silva, who has spent the bulk of her career characterizing the stinky, toxic molecule.

Sousa-Silva initially assumed that astronomers could search for phosphine as a biosignature on much farther-flung planets. “I was thinking really far, many parsecs away, and really not thinking literally the nearest planet to us.”

The team followed up Greaves’ initial observation using the more sensitive ALMA observatory, with the help of Anita Richards, of the ALMA Regional Center at the University of Manchester. Those observations confirmed that what Greaves observed was indeed a pattern of light that matched what phosphine gas would emit within Venus’ clouds.

The researchers then used a model of the Venusian atmosphere, developed by Hideo Sagawa of Kyoto Sangyo University, to interpret the data. They found that phosphine on Venus is a minor gas, existing at a concentration of about 20 out of every billion molecules in the atmosphere. Although that concentration is low, the researchers point out that phosphine produced by life on Earth can be found at even lower concentrations in the atmosphere.

The MIT team, led by Bains and Petkowski, used computer models to explore all the possible chemical and physical pathways not associated with life, that could produce phosphine in Venus’ harsh environment. Bains considered various scenarios that could produce phosphine, such as sunlight, surface minerals, volcanic activity, a meteor strike, and lightning. Ranjan along with Paul Rimmer of Cambridge University then modeled how phosphine produced through these mechanisms could accumulate in the Venusian clouds. In every scenario they considered, the phosphine produced would only amount to a tiny fraction of what the new observations suggest is present on Venus’ clouds.

“We really went through all possible pathways that could produce phosphine on a rocky planet,” Petkowski says. “If this is not life, then our understanding of rocky planets is severely lacking.”

A life in the clouds

If there is indeed life in Venus’ clouds, the researchers believe it to be an aerial form, existing only in Venus’ temperate cloud deck, far above the boiling, volcanic surface.

“A long time ago, Venus is thought to have oceans, and was probably habitable like Earth,” Sousa-Silva says. “As Venus became less hospitable, life would have had to adapt, and they could now be in this narrow envelope of the atmosphere where they can still survive. This could show that even a planet at the edge of the habitable zone could have an atmosphere with a local aerial habitable envelope.”

In a separate line of research, Seager and Petkowski have explored the possibility that the lower layers of Venus’ atmosphere, just below the cloud deck, could be crucial for the survival of a hypothetical Venusian biosphere.

“You can, in principle, have a life cycle that keeps life in the clouds perpetually,” says Petkowski, who envisions any aerial Venusian life to be fundamentally different from life on Earth. “The liquid medium on Venus is not water, as it is on Earth.”

Sousa-Silva is now leading an effort with Jason Dittman at MIT to further confirm the phosphine detection with other telescopes. They are also hoping to map the presence of the molecule across Venus’ atmosphere, to see if there are daily or seasonal variations in the signal that would suggest activity associated with life.

“Technically, biomolecules have been found in Venus’ atmosphere before, but these molecules are also associated with a thousand things other than life,” Sousa-Silva says. “The reason phosphine is special is, without life it is very difficult to make phosphine on rocky planets. Earth has been the only terrestrial planet where we have found phosphine, because there is life here. Until now.”

This research was funded, in part, by the Science and Technology Facilities Council, the European Southern Observatory, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Heising-Simons Foundation, the Change Happens Foundation, the Simons Foundation, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program.